Ultimate Guide: Impact of High Ambient Temperatures on Solar Battery Cycle Life: A Technical Guide to Maximizing Longevity

Impact of high ambient temperatures on solar battery cycle life: The Ultimate 2026 Technical Guide

The impact of high ambient temperatures on solar battery cycle life is the single most critical, yet frequently underestimated, variable in designing resilient and cost-effective energy storage systems (ESS). As we engineer the 2026 energy transition, moving toward mass adoption of distributed solar and storage, the conversation must elevate beyond simple kWh capacity and brand names. The technical imperatives now demand a granular understanding of electrochemical stability under thermal stress. For engineers, prosumers, and system architects, failing to properly model and mitigate thermal degradation is a direct path to catastrophic ROI failure, premature asset replacement, and compromised energy security. At SolarKiit, our mission is to build systems that endure, and that begins with a foundational, physics-first approach to thermal management. This guide moves beyond the superficial warnings found elsewhere; we will dissect the chemical reactions, quantify the financial implications, and benchmark the engineering solutions necessary to maximize the longevity of your solar battery investment. We will explore how a seemingly minor 10°C rise above the optimal operating temperature can cleave a battery’s expected lifespan in half, a costly lesson in thermodynamics that many are learning too late. This is not just about keeping a battery cool; it’s about preserving the delicate electrochemical balance that defines its value and performance over thousands of cycles. For a deeper look into our engineering philosophy, you can learn more about the team on our About page.

A Deep Technical Dive into Thermal Degradation Mechanisms

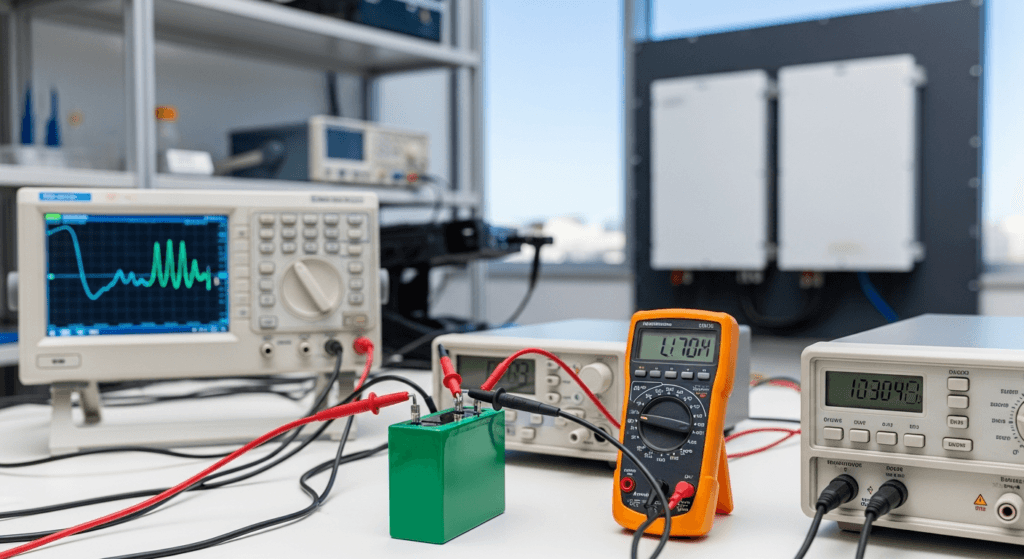

To truly grasp the severity of thermal impact, we must move beyond the black-box abstraction of a battery and into the realm of electrochemistry and solid-state physics. The degradation is not a simple linear process; it’s an exponential acceleration of parasitic reactions that permanently reduce a battery’s capacity and increase its internal resistance.

The Physics Behind the Impact of High Ambient Temperatures on Solar Battery Cycle Life

At its core, a Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) battery—the dominant chemistry for stationary storage due to its safety and longevity—operates through a process called intercalation. During discharge, lithium ions (Li+) travel from the graphite anode, through the electrolyte, and insert themselves into the crystal structure of the LiFePO4 cathode. The reverse happens during charging. This process is ideally 100% reversible.

However, temperature introduces kinetic energy that disrupts this elegant process. The rate of all chemical reactions, including undesirable ones, is governed by the Arrhenius equation. For every 10°C (18°F) increase in temperature above the ideal 25°C (77°F), the rate of these degradation reactions roughly doubles. The primary culprit is the accelerated growth of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) layer on the anode. This layer is necessary for stable operation, forming on the first few cycles, but excessive heat causes it to grow thicker and more resistive with every subsequent cycle. This parasitic growth does two things:

- Consumes Lithium: The formation of the SEI layer consumes active lithium ions, permanently removing them from the charge/discharge cycle. This directly translates to an irreversible loss of capacity. A battery rated for 10 kWh might only be able to store 9.5 kWh after a year in a hot garage, and this degradation accelerates.

- Increases Internal Resistance: The thicker SEI layer acts as an insulator, impeding the flow of lithium ions. This increased internal resistance means more energy is wasted as heat during charging and discharging (a lower round-trip efficiency), and it limits the battery’s ability to deliver high peak power for surge loads.

Simultaneously, high temperatures can degrade the electrolyte itself and cause structural damage to the cathode material, further crippling the battery’s performance. It’s a vicious cycle: higher ambient temperature increases internal resistance, which causes the battery to generate more internal heat during operation, further accelerating degradation. This is distinct from, but related to, the thermal coefficient of solar panels, where higher temperatures also reduce photon harvesting efficiency, as detailed in the NREL Best Research-Cell Efficiency charts.

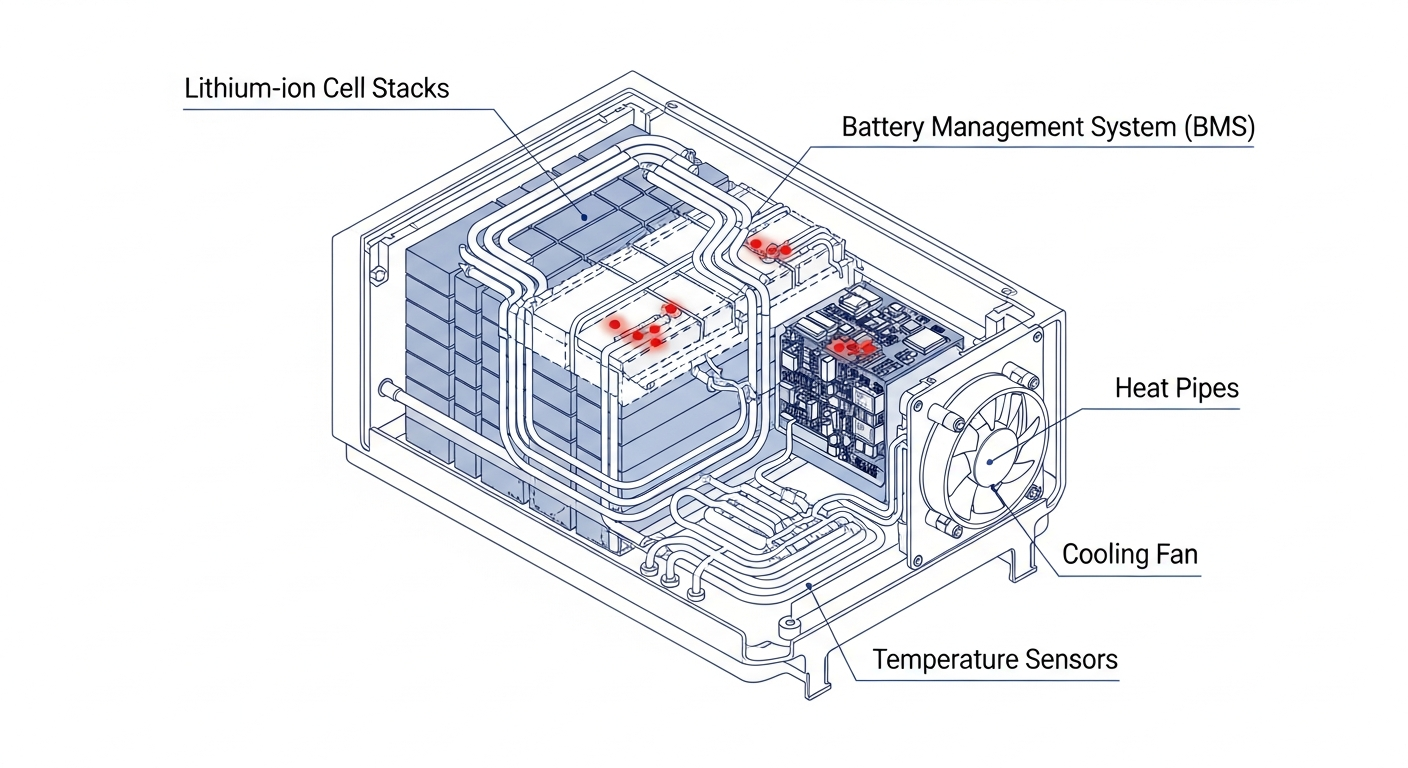

Component Synergy: The BMS, MPPT, and Inverter Handshake

A modern ESS is not just a battery; it’s a symphony of coordinated power electronics. The longevity of the system is dictated by how well these components communicate to manage thermal loads.

- Battery Management System (BMS): This is the brain. The BMS continuously monitors the voltage and temperature of every individual cell block. Its primary protective function is to enforce thermal limits. When cell temperatures exceed a pre-programmed threshold (e.g., 45°C), a sophisticated BMS will initiate “thermal derating,” actively signaling the inverter/charger to reduce the charging or discharging current. This proactive throttling prevents the cells from reaching critical temperatures that cause rapid degradation or safety hazards.

- MPPT Charge Controller & Inverter: These components must be able to receive and act upon the BMS’s commands. The handshake is critical. A high-quality hybrid inverter, like those we benchmark in our Solar Inverter Efficiency guide, has a dedicated communication bus (typically CAN bus) with the BMS. When the BMS requests derating, the inverter immediately limits the power it draws from the battery (for AC loads) or pushes into it (from solar or the grid). Without this seamless communication, the BMS is forced into a last-resort “thermal shutdown,” an abrupt disconnection of the battery that drops the entire system offline.

Engineering Math & Sizing for Thermal Resilience

Properly sizing a battery system for a hot climate goes beyond meeting the load; it involves building in a thermal resilience margin. Standard sizing formulas must be augmented with a thermal derating factor.

The baseline formula for battery capacity is:

Battery Capacity (kWh) = (Daily Energy Consumption (kWh) * Days of Autonomy) / (Depth of Discharge (DoD) * Round-Trip Efficiency)

To account for high-temperature environments, we introduce a Thermal Derating Factor (TDF). This factor, typically between 1.15 and 1.25 for hot climates, effectively oversizes the battery bank.

Thermally-Adjusted Capacity (kWh) = Base Capacity (kWh) * TDF

Why oversize? A larger battery bank means that for the same load profile, each individual cell is subjected to a lower C-rate (the rate of charge/discharge relative to capacity). A lower C-rate generates significantly less internal heat, keeping the cells closer to their optimal temperature and slowing the parasitic reactions discussed earlier. For example, powering a 3kW load with a 10kWh battery is a 0.3C discharge rate. Powering that same load with a thermally-adjusted 12.5kWh battery reduces the rate to 0.24C, which can be the difference between stable operation and thermal derating on a hot afternoon. This calculation is a core component of designing a comprehensive battery storage system for home use.

Key variables to calibrate:

- Load Profile: Analyze not just total kWh but peak demand and duration. A home with a 3-ton AC unit has a vastly different thermal impact on the battery than a home with the same total kWh consumption spread evenly.

- Surge Capacity: High temperatures can limit a battery’s ability to deliver the high surge currents needed for motor startup. Oversizing the bank ensures this capacity is available even when the BMS is limiting output.

- Days of Autonomy: In hot climates, this also provides a buffer against periods where the system may be thermally derated and unable to charge at its maximum rate.

Master Comparison Table: 2026 Solar Battery Models

To provide actionable data, we’ve benchmarked five leading battery models. The Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOE) is calculated to show the true cost per kWh delivered over the battery’s lifetime, a metric far more valuable than upfront price.

| Model | Chemistry | Nominal Capacity (kWh) | Cycle Life (@ 80% DoD, 25°C) | Thermal Operating Range (°C) | Estimated LCOE ($/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SolarKiit Titan X | LiFePO4 | 15.0 | 8,000 | -20°C to 60°C (Derating >45°C) | $0.12 |

| Tesla Powerwall 3 | LiFePO4 | 13.5 | 6,000 | -20°C to 50°C (Derating >40°C) | $0.15 |

| Enphase IQ 5P | LiFePO4 | 5.0 | 6,000 | -20°C to 55°C (Passive Cooling) | $0.18 |

| FranklinWH aPower | LiFePO4 | 13.6 | 6,000 | -20°C to 50°C (Derating >43°C) | $0.16 |

| LG RESU Prime | NMC | 16.0 | 4,000 | -10°C to 45°C (Tighter Limits) | $0.22 |

Regulatory & Safety Engineering for 2026 and Beyond

The increasing energy density of battery systems necessitates a rigorous adherence to safety standards, especially when considering thermal stress. Regulatory bodies are focused on preventing thermal runaway, a dangerous and self-sustaining chain reaction where a failing cell releases its energy as heat, causing adjacent cells to fail.

NEC 2026 and UL 9540/9540A Standards

Compliance is non-negotiable. The NFPA 70: National Electrical Code (NEC), particularly Article 706, provides the foundational rules for ESS installation. We anticipate the 2026 code cycle will introduce even stricter requirements for:

- Ventilation and Cooling (NEC 706.20): The code mandates that the installation environment must maintain the battery within its specified operating temperature range. This is not a suggestion. For systems installed in hot environments like a garage in Arizona or a shed in Florida, this often requires dedicated active ventilation or even mini-split HVAC systems, the power consumption of which must be factored into the system’s parasitic load.

- Spacing and Location (NEC 706.11): The code dictates minimum clearances around the ESS to allow for heat dissipation and service access. These clearances are often determined by the results of the UL 9540A test.

The UL Solutions (Solar Safety) standards are the gold standard for verifying safety. UL 9540 is the certification for the entire ESS as a unit, ensuring all components work together safely. UL 9540A is the critical large-scale fire test. An ESS that passes this test has proven its ability to contain a thermal runaway event at the cell level, preventing propagation to other cells or modules. This certification is paramount for installer confidence, homeowner safety, and obtaining approval from the local Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). Systems that pass UL 9540A often qualify for reduced spacing requirements, enabling more flexible and space-efficient installations.

Fire Safety and Mitigation Protocols

Engineering for fire safety is a multi-layered approach:

- Prevention: This is the primary goal, achieved through a robust BMS that prevents over-temperature, over-voltage, and over-current conditions.

- Containment: Using fire-retardant materials in the battery enclosure and providing physical separation between modules can slow or stop the spread of a thermal event.

- Suppression: Advanced systems incorporate integrated fire suppression systems, such as aerosol-based extinguishers, that can automatically deploy within the battery enclosure at the first sign of a thermal event, quenching the reaction before it can propagate.

The Pillar FAQ: Advanced Engineering Questions

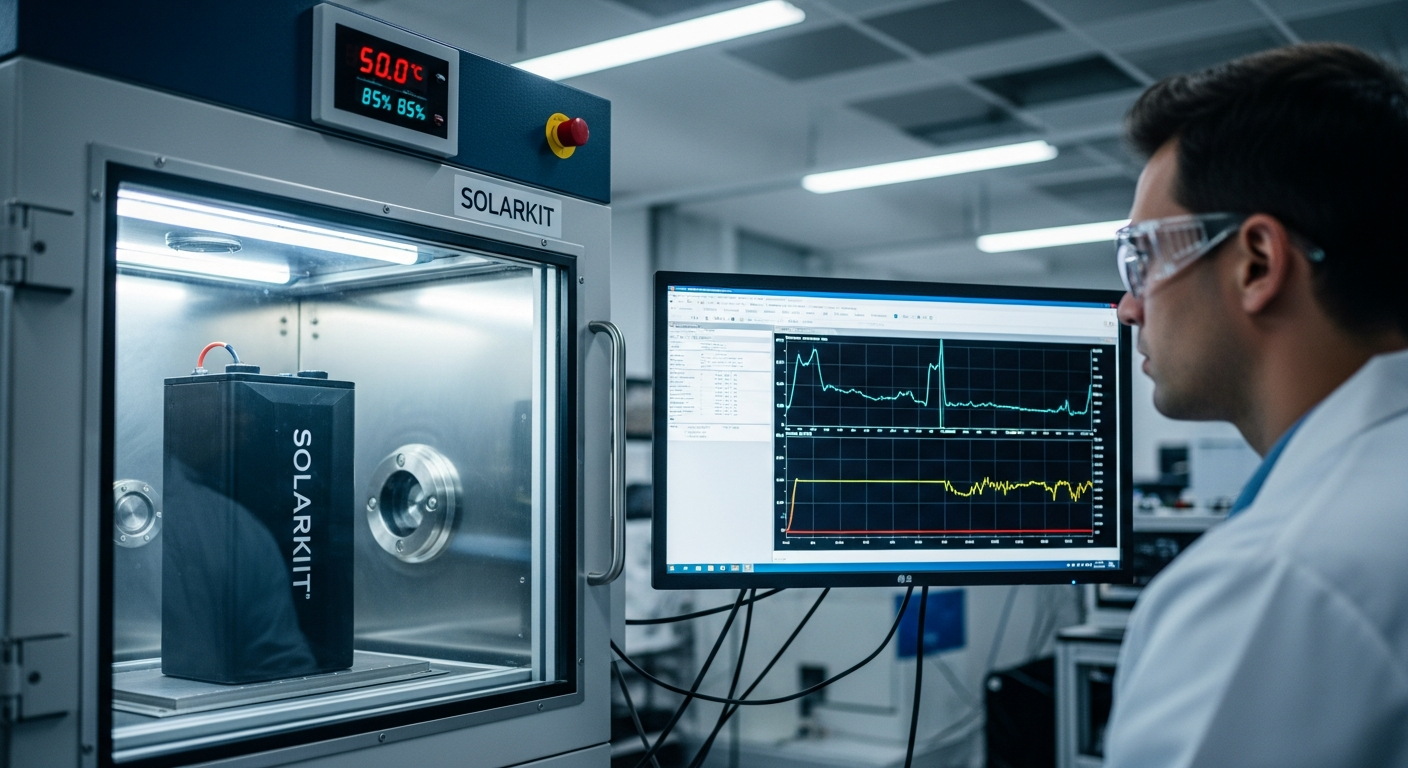

1. How does the Arrhenius equation specifically predict the accelerated degradation of LiFePO4 batteries in high temperatures?

The Arrhenius equation models the temperature dependence of reaction rates, predicting an exponential increase in the speed of parasitic side reactions within the battery as temperature rises. In the context of a LiFePO4 battery, the equation `k = A * e^(-Ea / RT)` is key, where `k` is the reaction rate constant, `Ea` is the activation energy for a specific degradation mechanism (like SEI growth), `R` is the universal gas constant, and `T` is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. The critical insight is the exponential term. This means that even a small increase in `T` causes a disproportionately large increase in `k`.

- For SEI layer growth, the activation energy (`Ea`) is relatively low, meaning the reaction is highly sensitive to temperature changes.

- As the rate constant `k` doubles for roughly every 10°C rise, the rate at which active lithium is consumed and internal resistance grows also doubles.

- This allows engineers to model and predict capacity fade. A battery warrantied for 6,000 cycles at 25°C might only deliver 3,000-3,500 effective cycles if its average operating temperature is 35°C, a direct and quantifiable consequence predicted by this fundamental chemical principle.

2. What is the technical difference between “thermal derating” and “thermal shutdown” in a BMS, and how do they impact system usability?

Thermal derating is a proactive, controlled reduction of power to manage heat, while thermal shutdown is a reactive, emergency disconnection to prevent catastrophic failure. Their impact on the user experience is vastly different.

- Thermal Derating: This is an intelligent, graceful system response. The BMS detects rising cell temperatures and communicates with the inverter to gradually reduce the charge/discharge current. The system remains online, but at a reduced capacity. For the user, this might mean their home’s AC unit cycles off temporarily or the battery charges more slowly on a hot, sunny day. It’s a compromise that prioritizes battery health over maximum performance.

- Thermal Shutdown: This is the last line of defense. If derating is insufficient or not possible (due to a communication failure), the BMS will open its contactors, completely and abruptly disconnecting the battery from the inverter. For the user, this means an immediate and total loss of battery power. The home loses its backup power source, and any solar power being generated may also be curtailed if the inverter has nowhere to send it. It is a severe event that indicates the system is operating far outside its design parameters.

3. Can active cooling systems, like liquid cooling, actually have a negative ROI by consuming too much parasitic power?

Yes, an improperly designed active cooling system can consume enough energy to negate the longevity benefits it provides, resulting in a negative ROI. The key is to benchmark the parasitic load against the extended lifespan. For most residential ESS, aggressive liquid cooling is overkill. A well-designed system using variable-speed fans, strategic air channels, and intelligent BMS control offers the best balance.

- Parasitic Load Calculation: A typical variable-speed fan system might consume 30-60 watts when active. Over a year in a hot climate, this could be 50-100 kWh of energy. A liquid cooling pump could consume significantly more.

- ROI Analysis: We must compare this energy cost to the value of the extended cycle life. If active cooling extends a $10,000 battery’s life from 8 years to 12 years, the financial benefit is substantial. However, if the cooling system is inefficient and the climate is moderate, the energy cost could exceed the marginal value of the extra cycles gained.

- Optimal Solution: The best engineering solution is adaptive cooling. The system should rely on passive convection for as long as possible and only engage fans (at variable speeds) when specific cell temperature thresholds are crossed, minimizing the parasitic load while ensuring the battery remains in its optimal 20-30°C range.

4. Beyond cycle life, how does high ambient temperature affect a battery’s Round-Trip Efficiency (RTE) and why?

High ambient temperature directly reduces Round-Trip Efficiency by increasing the battery’s internal resistance, causing more energy to be lost as heat during both charging and discharging. RTE is the ratio of energy out to energy in, and this loss is a direct financial hit. The mechanism is rooted in physics: `Power Loss = I²R`, where `I` is the current and `R` is the internal resistance.

- As explained earlier, heat accelerates the growth of the resistive SEI layer, permanently increasing the battery’s baseline `R`.

- Furthermore, the resistance of the electrolyte itself has a temperature dependency. While it decreases slightly with initial warming, excessive heat can begin to degrade the electrolyte, increasing resistance.

- During a high-power discharge on a hot day, this elevated `R` means a larger portion of the stored energy is converted to waste heat instead of usable power. The same is true for charging. A system with a 95% RTE at 25°C might drop to 92% or lower at 40°C. Over a 15-year lifespan, this 3% loss represents thousands of kilowatt-hours of wasted energy.

5. How will upcoming solid-state battery chemistries change the engineering considerations for the impact of high ambient temperatures on solar battery cycle life?

Solid-state batteries promise to fundamentally alter thermal management by offering wider operating temperature ranges and eliminating flammable liquid electrolytes, though they introduce new engineering challenges. The primary advantage is their potential for enhanced thermal stability.

- Wider Operating Window: Many solid-state electrolytes (like sulfide- or polymer-based) are stable at much higher temperatures than their liquid counterparts, potentially operating efficiently up to 80°C or even 100°C. This could drastically reduce or even eliminate the need for active cooling in many climates, simplifying system design and eliminating parasitic loads.

- Inherent Safety: By removing the flammable liquid electrolyte, the primary fuel for thermal runaway is eliminated. This makes the batteries inherently safer and could ease regulatory burdens under standards like UL 9540A.

- New Challenges: However, challenges remain. Many solid-state designs face issues with dendrite formation at high charge rates. Furthermore, maintaining consistent physical contact between the solid electrolyte and the electrodes during thermal expansion and contraction is a significant mechanical engineering problem. Therefore, while the nature of the problem will shift from preventing electrolyte breakdown to managing mechanical stress and interface integrity, understanding and controlling the impact of high ambient temperatures on solar battery cycle life will remain a critical discipline.

📥 Associated Resource:

El Kouriani Abde Civil Engineer & Founder of SolarKiit

El Kouriani Abde is a seasoned Civil Engineer and Project Manager with over 21 years of field experience. As the founder and publisher of SolarKiit.com, he leverages his deep technical background to simplify complex renewable energy concepts. His mission is to provide homeowners and professionals with accurate, engineering-grade guides to maximize their solar investments and achieve energy independence.