Panneaux Solaires : Le Guide Complet 2026 pour l’Autoconsommation

As we advance into 2026, the paradigm of residential energy is undergoing a fundamental transformation. The concept of “autoconsommation,” or self-consumption, has evolved from a niche pursuit for environmental enthusiasts into a strategic imperative for energy security and financial prudence. This guide provides a comprehensive engineering analysis of the technologies, specifications, and strategies defining the 2026 solar self-consumption landscape, with a primary focus on the cornerstone of modern energy independence: battery storage.

Strategic Overview: The 2026 Energy Sovereignty Mandate

The 2026 solar market is no longer solely driven by the declining Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) from photovoltaics. It is now defined by a confluence of grid instability, volatile utility pricing, and the maturation of energy storage systems (ESS). The primary driver for residential solar adoption has shifted from simple grid-tied net metering to sophisticated solar-plus-storage configurations that maximize self-consumption and provide critical backup power.

In this landscape, Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) battery chemistry has become the undisputed industry standard for residential applications. Its superior thermal stability, long cycle life, and freedom from conflict minerals like cobalt have made it the go-to technology. The market is moving beyond simple energy arbitrage (storing cheap solar energy for evening use) and towards more advanced use cases like participation in Virtual Power Plants (VPPs), where aggregated residential batteries provide ancillary services to the grid for financial compensation.

Achieving “energy sovereignty” is the new objective. This means not just generating your own power, but intelligently managing its storage and dispatch to insulate your home from grid failures and price shocks. The 2026 homeowner is not just a consumer but a “prosumer,” an active participant in a decentralized energy grid. This guide focuses on the technical acumen required to design, specify, and operate such a system effectively.

Deep Technical Analysis: From Photons to Kilowatt-Hours

The Physics of Photovoltaic Conversion and Storage

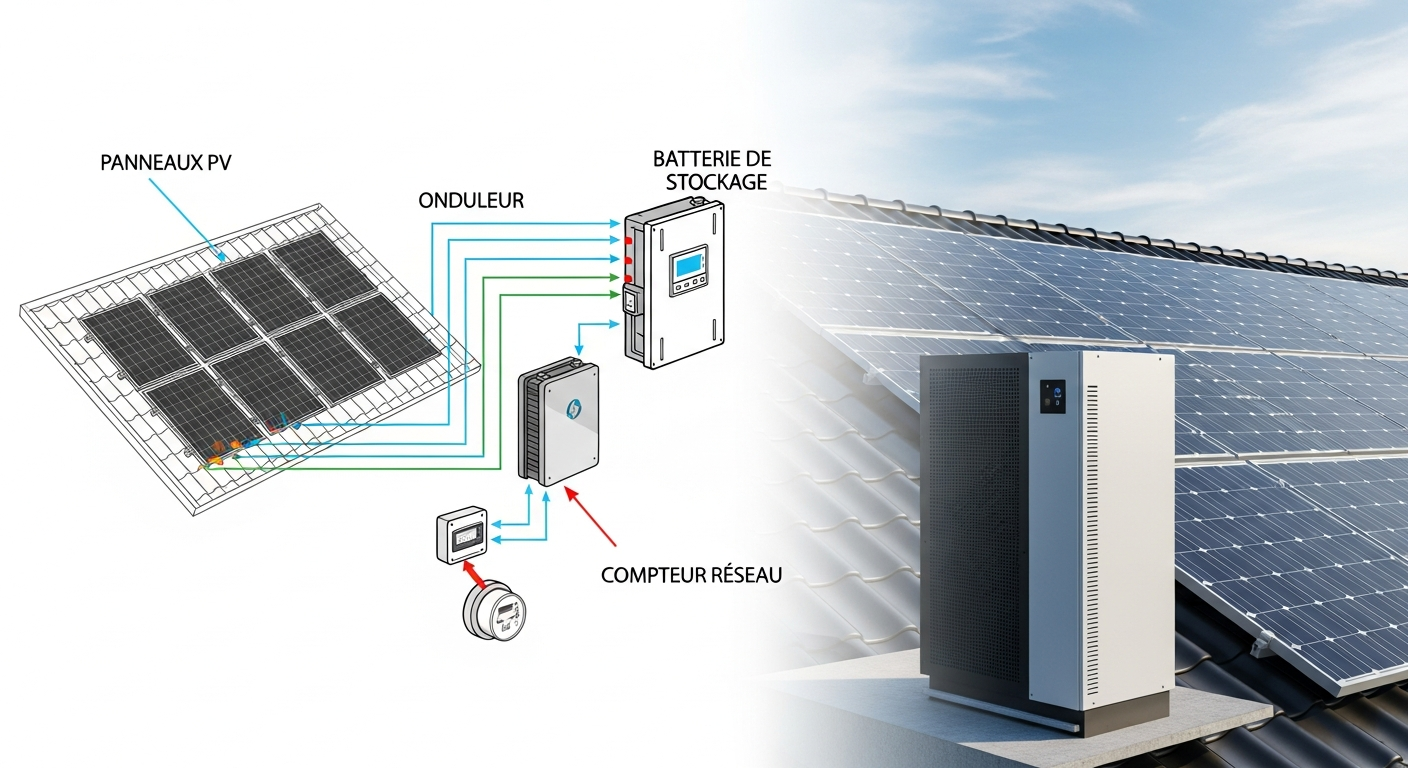

At its core, a solar self-consumption system is a multi-stage energy conversion process. It begins with the photovoltaic (PV) effect. When photons from solar irradiance strike a semiconductor material (typically silicon) within a PV cell, they transfer their energy to electrons, creating electron-hole pairs. The cell’s internal electric field, established by a p-n junction, separates these pairs, forcing the electrons to flow through an external circuit. This flow of electrons constitutes a direct current (DC).

This DC power is then managed by a charge controller or, more commonly in 2026, a hybrid inverter. The primary function is to convert this variable DC output from the PV array into a stable DC voltage suitable for charging the battery bank. The hybrid inverter then performs a second critical conversion: inverting the DC power (from either the PV array or the battery) into a grid-synchronous, pure sine wave alternating current (AC) at the appropriate voltage (e.g., 120/240V at 60Hz in the US) to power household loads.

A pure sine wave output is non-negotiable for modern systems. Unlike a modified sine wave, which is a stepped approximation, a pure sine wave is essential for the proper and efficient functioning of sensitive electronics, variable-speed motors in appliances, and medical equipment. The total harmonic distortion (THD) of a high-quality inverter in 2026 should be less than 3%.

Efficiency Benchmarks and Performance Metrics for 2026 Systems

System efficiency is a product of the efficiencies of its individual components. By 2026, benchmarks have reached impressive levels. High-efficiency N-type TOPCon (Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact) and HJT (Heterojunction) solar panels now dominate the premium residential market, with commercially available module efficiencies consistently exceeding 24%. The lab-to-market pipeline is beginning to introduce the first generation of Perovskite-on-Silicon tandem cells, promising module efficiencies approaching 30%.

Inverter efficiency is equally critical. Top-tier hybrid inverters from manufacturers like Victron and Sol-Ark boast peak efficiencies greater than 98%. However, it is the California Energy Commission (CEC) weighted efficiency that provides a more realistic performance metric, averaging efficiency across a range of operating loads. Look for CEC efficiencies above 97%.

For battery storage, the key metric is Round-Trip Efficiency (RTE), which measures the energy recovered during discharge relative to the energy supplied during charging. For 2026-era LiFePO4 battery systems, an RTE of 95% or higher is the standard. This means for every 10 kWh of solar energy sent to the battery, at least 9.5 kWh is available for later use, a significant improvement over the sub-85% RTE of legacy lead-acid technologies.

System Sizing and Load Calculation Strategy

Proper system sizing is the most critical step in engineering a successful self-consumption system. It begins with a meticulous load calculation and energy audit. This involves analyzing 12-24 months of utility bills to determine average daily energy consumption in kilowatt-hours (kWh) and identifying peak demand in kilowatts (kW). For new construction, this must be estimated based on appliance specifications and usage patterns.

The PV array must be sized to meet or exceed this daily energy demand, accounting for system losses and location-specific solar irradiance (known as Peak Sun Hours). A common formula is: Array Size (kWp) = (Daily Energy Consumption in kWh) / (Average Peak Sun Hours) / 0.85 (derating factor for losses). Tools like the NREL’s PVWatts calculator are indispensable for determining accurate local irradiance data based on PV orientation (azimuth) and tilt angle.

Battery capacity is sized based on the desired level of autonomy and the operational strategy. For load-shifting, a battery might be sized to cover evening and nighttime loads. For full backup, it must be sized to cover critical loads for a specified number of days. A fundamental calculation is: Required Usable Capacity (kWh) = (Daily Critical Load kWh * Days of Autonomy) / (Battery Depth of Discharge). For LiFePO4, the Depth of Discharge (DoD) can be safely set to 90-100%, maximizing usable capacity.

Finally, voltage drop must be calculated for long DC cable runs between the PV array and the inverter. Using an insufficient wire gauge (e.g., a high AWG number for a long run) can lead to significant power loss and a safety hazard. Per NEC guidelines, voltage drop should be kept below 3% for optimal performance.

Engineering Specifications & Innovations in 2026

The market is dominated by vertically integrated solutions and highly specialized components that push the boundaries of performance. By 2026, several key players have established distinct technological advantages.

Tesla’s Powerwall 3 represents the pinnacle of integration. Its key innovation is the inclusion of an 11.5 kW hybrid inverter directly within the battery unit. This simplifies installation, reduces component count, and creates a seamless ecosystem. Its liquid thermal management system allows for high power output and longevity, even in harsh climates, setting a benchmark for residential energy storage.

EcoFlow’s PowerOcean system champions modularity and high power. Built around a 3-phase hybrid inverter and stackable 5 kWh LiFePO4 battery packs, it allows homeowners to scale their storage from 5 kWh to 45 kWh. Its standout feature is the ability to provide up to 10 kW of backup power per battery pack, ensuring that even high-draw appliances like HVAC systems can be supported during an outage.

Victron Energy continues its reign in the professional and off-grid sectors. Their MultiPlus-II inverter/charger is a testament to robust engineering, offering unparalleled configuration flexibility. When paired with CAN-bus compatible batteries like those from Pylontech or BYD, the system allows for precise state-of-charge control and advanced grid-forming capabilities, essential for creating a stable, independent microgrid.

On the materials science front, Perovskite-on-Silicon tandem solar cells are the most significant innovation. By layering a thin film of perovskite material atop a traditional silicon cell, these tandem cells can capture a broader spectrum of light. The perovskite top cell efficiently converts high-energy blue and green light, while the silicon bottom cell captures the remaining red and infrared light, breaking past the Shockley-Queisser limit for single-junction cells and pushing practical efficiencies toward the 30% mark.

In battery chemistry, while LiFePO4 is dominant, Sodium-Ion (Na-ion) batteries are emerging as a viable alternative for stationary storage. Though they have a lower energy density than LFP, they offer excellent cycle life, a wider operating temperature range, and are manufactured from abundant, inexpensive materials (sodium instead of lithium). This makes them a compelling future option for cost-effective, large-scale residential storage.

Technical Comparison: 2026 Residential Energy Storage Systems

| Model (2026 Spec) | Battery Chemistry | Usable Capacity (kWh) | Continuous Power (kW) | Round-Trip Efficiency | Cycle Life (at 90% DoD) | Warranty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla Powerwall 3 | LiFePO4 | 13.5 kWh | 11.5 kW | 97.5% | >6,000 cycles | 15 years, 70% retention |

| EcoFlow PowerOcean | LiFePO4 | 5-45 kWh (modular) | 10 kW | 95% | >6,000 cycles | 15 years, 70% retention |

| Enphase IQ Battery 5P | LiFePO4 | 5.0 kWh (modular) | 3.84 kW | 96% | >6,000 cycles | 15 years, 60% retention |

| Bluetti EP900 + B500 | LiFePO4 | 9.9-19.8 kWh (modular) | 9 kW | 94% | >5,000 cycles | 10 years, 80% retention |

| Victron MultiPlus-II w/ Pylontech US5000 | LiFePO4 | 4.5 kWh per unit (scalable) | 4 kW (per inverter) | 95% (system) | >6,000 cycles | 5-10 years (component-based) |

Safety, Standards, and Code Compliance

A high-performance solar and storage system must be engineered with an unwavering commitment to safety. Compliance with national and international standards is not optional. In the United States, the National Electrical Code (NEC) provides the foundational safety requirements for all installations.

NEC Article 690 (Solar Photovoltaic Systems) and NEC Article 706 (Energy Storage Systems) are the primary governing documents. A key requirement is NEC 690.12 (Rapid Shutdown), which mandates a method for de-energizing PV system conductors to a safe voltage level within seconds. This is a critical safety feature to protect first responders during an emergency.

Component-level certifications are paramount. All energy storage systems must be certified to UL 9540, the Standard for Energy Storage Systems and Equipment. This standard ensures the battery, inverter, and control systems work together safely. Furthermore, the battery cells themselves should be tested according to UL 9540A, which is a test method for evaluating thermal runaway fire propagation. The superior thermal stability of LiFePO4 chemistry makes it far less prone to thermal runaway than older chemistries like Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC).

Ingress Protection (IP) ratings are also a critical specification. An outdoor-rated inverter or battery enclosure should have a minimum rating of IP65, signifying it is dust-tight and protected against water jets from any direction. Connectors and other critical components exposed to the elements may require an IP67 rating, indicating they can withstand temporary immersion in water. Physical protection, such as installing bollards to prevent vehicle impact and maintaining manufacturer-specified clearances for ventilation, is also a mandatory part of a safe installation.

Pre-Installation Engineering Checklist

A successful project is built on meticulous planning. Before any hardware is ordered, a thorough pre-installation process must be completed. This checklist outlines the essential engineering and logistical steps for homeowners and installers.

- Professional Site Survey: A qualified engineer must conduct a detailed site survey to assess solar access (shading analysis), determine optimal PV array placement (azimuth and tilt), and identify the location for the inverter and battery system.

- Structural Engineering Assessment: The roof structure must be professionally evaluated to confirm it can support the additional dead load of the PV array and mounting hardware, especially in areas with high snow load requirements.

- Electrical System Evaluation: An electrician must inspect the main electrical service panel to ensure it has the capacity and physical space to accommodate the back-fed solar breaker and any necessary sub-panels for critical loads.

- Load Profile Analysis: Complete a comprehensive energy audit to accurately size the PV array and battery capacity. This prevents costly under-sizing or over-sizing of the system.

- Permitting and Utility Interconnection: Secure all necessary building and electrical permits from the local Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). Simultaneously, submit the interconnection application to the local utility to ensure a seamless grid connection process.

- Component Specification and Verification: Finalize the bill of materials, ensuring all components (modules, inverter, battery, racking, wiring) are certified, compatible, and meet the project’s specific performance and safety requirements.

Advanced Technical FAQ

What is the difference between AC-coupled and DC-coupled battery systems?

AC-coupling involves adding a battery and a separate battery inverter to an existing grid-tied solar system. The solar inverter converts PV DC to AC, and the battery inverter converts it back to DC to charge the battery. To use the stored energy, it’s inverted back to AC again. This “triple conversion” leads to lower round-trip efficiency but is excellent for retrofitting. DC-coupling, common with hybrid inverters, connects the PV array, batteries, and inverter on a common DC bus. This is more efficient (fewer conversions) and is the standard for new solar-plus-storage installations.

How does a hybrid inverter differ from a string inverter and microinverters?

A string inverter converts DC power from a “string” of solar panels into AC power. Microinverters are small inverters installed on each individual panel, converting DC to AC at the source. A hybrid inverter is a more advanced device that combines the functionality of a string inverter and a battery inverter. It can simultaneously manage power flow from the PV array, the battery bank, the utility grid, and the home’s loads, making it the central brain of a modern self-consumption system.

What is “Depth of Discharge” (DoD) and how does it impact my LiFePO4 battery’s lifespan?

Depth of Discharge (DoD) refers to the percentage of the battery’s total capacity that has been discharged. A 10 kWh battery discharged by 9 kWh has a 90% DoD. While deep discharging significantly shortens the life of lead-acid batteries, LiFePO4 chemistry is highly resilient. A modern LiFePO4 battery can typically handle 6,000 or more cycles at a 90% DoD while retaining 70-80% of its original capacity. This ability to be deeply discharged is what makes them so effective for daily cycling in a self-consumption application.

Is it technically feasible to go completely off-grid with a residential solar and battery system?

Yes, it is technically feasible but requires significant engineering and investment. An off-grid system must be oversized to handle consecutive cloudy days, meaning a much larger PV array and battery bank than a grid-tied system. It must also be capable of handling “inrush current” from large motors starting up. Most true off-grid systems also incorporate a backup generator (propane or diesel) for reliability during extended periods of low solar production. The cost is substantially higher than a grid-tied system with backup capabilities.

What are Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) and how can my battery participate?

A Virtual Power Plant (VPP) is a network of decentralized, residential energy storage systems that are aggregated and controlled by a central operator to provide services to the electrical grid. When the grid is stressed, the VPP can instruct thousands of home batteries to discharge simultaneously, providing rapid demand response or frequency regulation. Homeowners who enroll their batteries in a VPP program are typically compensated for this service, creating a new revenue stream and reducing the payback period of their investment.

📥 Associated Resource:

El Kouriani Abde Civil Engineer & Founder of SolarKiit

El Kouriani Abde is a seasoned Civil Engineer and Project Manager with over 21 years of field experience. As the founder and publisher of SolarKiit.com, he leverages his deep technical background to simplify complex renewable energy concepts. His mission is to provide homeowners and professionals with accurate, engineering-grade guides to maximize their solar investments and achieve energy independence.